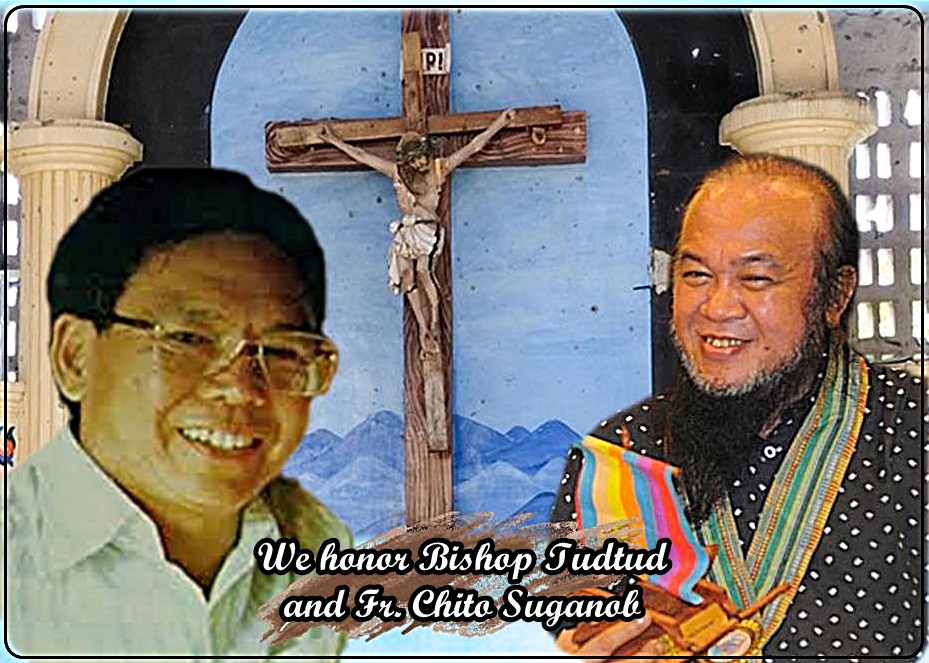

A few days ago, Fr. Chito Suganob passed away. He was a living testimony of dialogue in Marawi before the siege, during the siege up to his death. He was an active member of the Silsilah Forum Marawi before the siege and he visited us in Zamboanga after the siege and renewed his commitment and mission of dialogue.

Bishop Bienvenido S. Tudtud was also a friend of Fr. Sebastiano D’Ambra, the founder of Silsilah Dialogue Movement and he was the one who told him to be patient in this mission of dialogue and added: “This is a mission of 100 years”. He was in Zamboanga on May 30, 1987 on the occasion of the first Summer Course and he left Zamboanga to go for a meeting in Baguio and he died in a plane crash on the way to Baguio on June 26, 1987. All of us also remember the painful experience of the siege in Marawi that still causes so much pain to many who lost everything on that occasion and the suffering of Fr. Chito with other Christian hostages.

In a recent ZOOM symposium organized by the University of Sto. Tomas, CBCP-Episcopal Commission for Interreligious Dialogue, Prelature of Marawi and Uni-Harmony Partners Manila. Fr. D’Ambra in his welcome address reminded the participants of the prophetic vision pf the Prelature of Marawi in 1982 prepared by Bishop Bienvenido “Ben” Tudtud commonly called, “Tatay Bido”.

Remembering Bishop Tudtud and Fr. Chito, we decided to present here the full text of the Vision of dialogue of the Prelature of Marawi. Both of them lived and shared their lives living this vision.

This document is a “prophetic” vision of Bishop Bienvenido Tudtud (1982) to inspire the small community of Christians in the Prelature of Marawi in Mindanao.

Bishop Tudtud challenged the members of the assembly of the Prelature of Marawi to share and write down their ideas, feelings and dreams about dialogue. They did it in four separate groups: the priests, the sisters, the teachers and the rest of the lay workers. Bishop Tudtud then collected all that was written and he composed the text that we now present. This text became the basis for all further deepening on dialogue during the Prelature meetings of the following years.

This is the full text of the Prelature Vision of Marawi:

- To be loved by God and to be able to love Him in return -this is a human experience as real as it is mysterious. This divine and human exchange is actually the essence of what Christians call “The Good News” and of what Muslims mean when they refer to God as the Merciful (Al-Rahman), the Compassionate (Al-Rahim), and the Loving One (Al- Wadud). To hold and believe it is faith. To announce and proclaim it is an integral part of the mission of Christianity and of the da’wah of Islam.

- Any good human activity such as preaching and teaching can be a vehicle for communicating the good news about God’s love. The nobler the activity, the more credible the message. Man becomes more fully human when he relates the love of God in true communion with another. This is dialogue.

- In the best of times during his earthly existence, given man’s thirst for growth and perfection, he needs both to proclaim and to hear about God as the Loving One. Every gift received from God is good. Every good must somehow be communicated. Belief in the divine mercy and compassion must be shared. This sharing is dialogue. When brothers tell one another how good God has been to them, the bonds that are thereby created are really new gifts, fresh manifestations of the Divine Largesse.

- In today’s situation of conflict, sharing the experience of God’s love through dialogue becomes all the more imperative. Where deep chasms and high walls exist, the Divine Goodness can hard begin to be proclaimed, much less heard and understood. Dialogue is a way of building bridges and breaking down walls.

- In a situation of prejudice, dialogue means an abiding and genuine search for goodness, beauty and truth. This search is based on the conviction that no one person has a monopoly of these. For are not goodness, beauty and truth emanating from one and the same source, God? Who or what can monopolize Him? Thus each person must be open to the fact that he can be enriched by the goodness, beauty and truth found in the other. Each must be ready to discover the face of God in the other’s faith.

- In an atmosphere of animosity dialogue means powerlessness and vulnerability. From a position of power one can only negotiate about terms. From a position of weakness one can truly communicate his trust in the other. Trust is most real when there looms the possibility of betrayal. To dialogue means to open one’s heart. This is a position of vulnerability. This is a high risk which must be taken by anyone who wants to enter into genuine dialogue.

- In a situation of elitism in all aspects of human life – social, political, economic, cultural and even religious – dialogue demands a preferential option for the poor, the voiceless, the powerless. The vast majority of the population is marginalized even in the core element of their existence. They are not allowed to define their meanings, to assert what things can have real value in their lives. To this vast majority must God’s love and mercy come as good news and an inspiration in their struggle to liberate themselves. In them must the explicit believer discover the face of God. To them must dialogue be first offered.

- To be wounded in the act of loving, to understand in a climate of misunderstanding, to trust in an atmosphere of suspicion – these are no light burdens to bear. Dialogue therefore demands a deep spirituality which enables man to hang on to his faith in God’s love, even when everything seems to fall apart. This spirituality is such that what is believed in the heart becomes alive in one’s style of life.

- This same dialogue demands a deep respect for the faith of others, for the way they understand it, and also for the manner in which they express it. The faith of the others may not be judged from the perspective and categories of one’s own faith. Thus dialogue also demands serious study of the faith and religion of others, as well as one’s own.

- In an area where Muslims and Christians live together, the dialogue described above is an offering to both. It is an offering because though it is a demand on the believer, he should not force it on those with whom he must relate.

- It is an offering because it is ever extended not only in the pleasantness of appreciation but also in, and even beyond, the pain of rejection. Dialogue is an offering because it respects the antipathies of both Muslims and Christians and the pace with which they strive to ease their hurts and to heal their wounds. Here dialogue is compassion.

- Besides being an offering, dialogue is a challenge as well. It asks of a believer whether his faith does not require him to rise above his prejudices, even those that stem from real pain. It is a challenge to scrutinize the pain-filled past yet hope still to start a new chain of happy memories for tomorrow.

- Dialogue is above all a communion of men in total surrender to God, who persist in the hope that all can have a change of heart and participate in the building of God’s Kingdom whose completion He alone can bring about.